Of course, Rhinoceros (1974) directed by Tom O'Horgan and starring Gene Wilder and Zero Mostel (in that order) is not really any kind of a film, nor was it meant to be. It was part of the series of hyper-faithful filmed plays produced by Eli Landau for a limited subscription run. The result was a bastard form, neither film nor play (really a sort of television show) and the death of the project was not unexpected.

In a way, the films based on texts in another language, as was Rhinoceros had an inherent license to be freer with their adaptations, within the limited budgets of the films. The film did not use an existing translation, but commissioned an original script from Julian Barry, who had recently collaborated with O'Horgan on the play Lenny (a biography of Lenny Bruce eventually to become a film by Bob Fosse). Yet the film adheres to the play's settings, character and three-act structure with a half-hearted transliteration of French names and institutions into American ones.

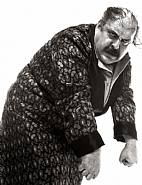

What the film has is a record, albeit flawed, of Zero Mostel's performance as Jean (John), the elegant, sophisticated man of the world who joins in with the rest of the population to become a rhinoceros. Unlike the other characters, Jean undergoes the transformation on stage/on camera. In the New York theater, this role, along with Leo Bloom Ulysses in Nighttown brought Zero Mostel back to prominence after a decade of languishing on the blacklist. I had heard about this performance, read descriptions by critics like Walter Kerr and was a fan of Lenny to boot, so I was really looking forward to this film in January 1974 when I went to see it.

Back then it was a terrible disappointment. The film looked cheap (it was) and felt like a never-ending talkfest (it sort-of is). Mostel's transformation was fun, but not shot or lit very well (still true) and after his departure, the film felt as though it took a terrible slide. The problem was compounded by the "groovy" contemporary music of Galt MacDermot (Hair), who was permitted to insert a song toward the end of the film, which unfortunately nails the film to the period of the early-mid 1970s.

But the passage of time has improved the movie. The growing presence of the rhinoceroses is clean-limbed and easy to follow; beginning as a fringe movement easily dismissed and growing into something impossible to ignore. Mostel's light and airy style of movement in the first part of the film recalls Disney's dancing hippos in Fantasia. Wilder's free-floating anxiety, so apparent in this part of his career is perfectly employed as Berger (here called Stanley), Ionesco's all-purpose mediocrity. Similarly Karen Black's descent into rhinocerosism is clearly laid out and obviously inevitable. The cheap effects still look cheap and the vaudeville acting of Joe Silver and Robert Weil are still miscalculated for the camera (the director's fault, not the actors'), but they are lively and fun, not as tedious as I felt. I wondered why this film seemed to grind on for me back then, whereas it bumps along nicely now -- usually the opposite happens to films over time. What was I waiting for, hoping for?

Or maybe back in the 1970s, the danger of conformity seemed at a low ebb. Everybody was doing their own thing, the institutions of society and government were in disarray and what was bugging Ionesco in the 1950s seemed to have been conquered. Now after years of Reaganism and now the hysteria over terrorism, dissent is being squelched again, and everyone is expected to toe the line again, at least on issues like security and Fear of Brown People, which is gripping the minds of America's Chicken Littles at the moment. Suddenly Rhinoceros speaks again, and for myself, I can sympathize with poor Stanley/Berger, who would dearly like to become a rhinoceros like everyone else but cannot. So he is left alone, an individual not from conviction but from inability to become what he is not.

To talk about the film of Rhinoceros is to spend too much space talking about what could have or should have been -- perhaps animation or special effects or some way to make a cinematic equivalent to the stage's natural penchant for fantasy. The problem of adapting a play like this is probably insoluble. Cinema fantasy is a concrete affair and not given to poetry, even the angry poetry of Ionesco. But to see Mostel and Wilder in their only pairing after The Producers, both eminently well cast and doing their best to make it all go makes one grateful both for the effort and the for the modest pleasures to be found therein.

No comments:

Post a Comment